By Lynn Ascrizzi

Resilience. A capacity to flourish. Hidden strength. Attributes like these are native to the aspen tree: a lithe, adaptable species that announces spring with flowering catkins, reclaims burned-over, scarred landscapes and, in fall, lights up hillsides with bright-gold leaves.

The tree’s hardy attributes seem to be a fitting metaphor for Aspen Saddlery of Rineyville, Kentucky, a one-man shop owned and operated with single-minded dedication by saddlemaker and leatherworker, Ben Geisler.

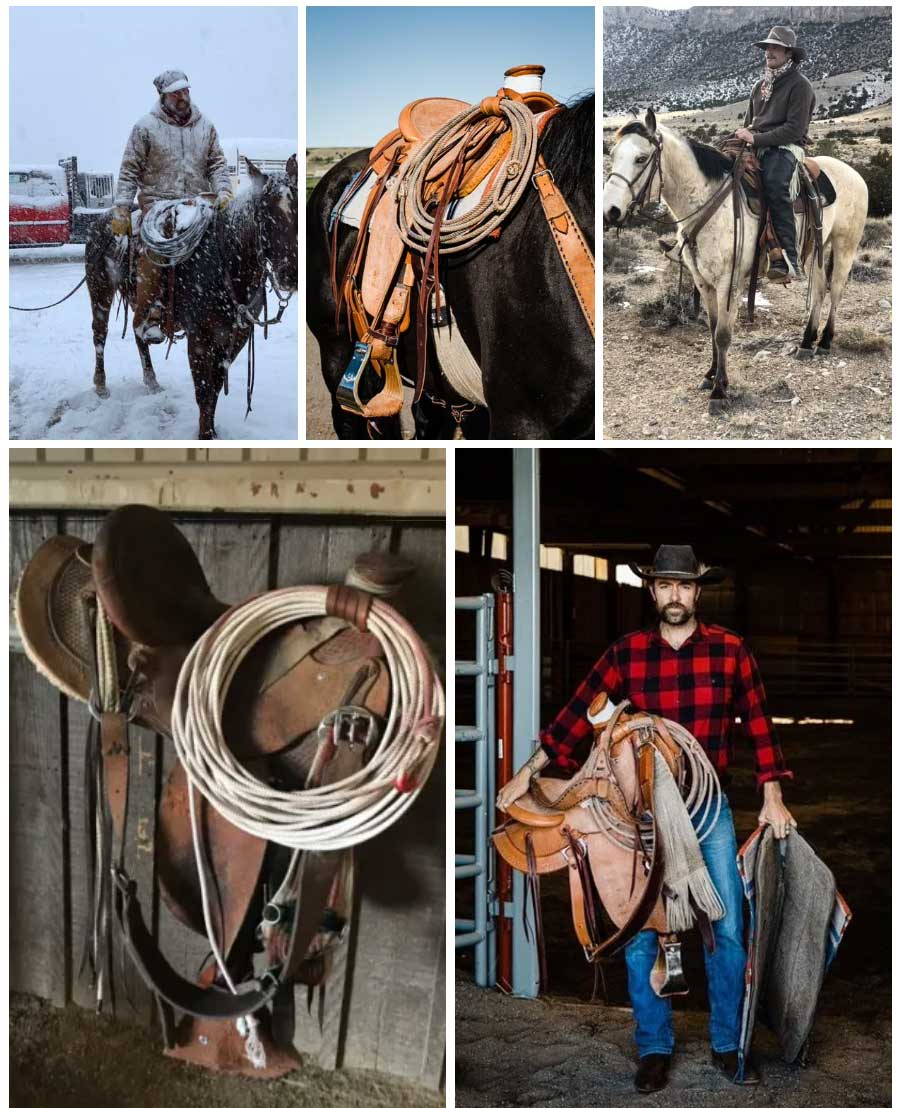

The majority of Geisler’s equally hardy customers are ranch cowboys and horse trainers. “I make working saddles for working horsemen. They’re almost all rough-out, Wade saddles, made flesh side-out. The thing with rough out, is that it gives the rider more grip. It doesn’t necessarily scratch or mark. Over time, it will smooth down. It’s an honor for me to make something that helps another person make a living,” he said.

Geisler does not hire help. “It’s my work only. I stamp my name on every piece. You need to take ownership for everything you do. It’s both liberating and terrifying,” he said.

The Wade saddle, he noted, was first introduced in Oregon in the late 1930s. The style soon caught on with horsemen in nearby states and beyond. “Wade saddles first came into wide use in Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, California and Idaho — the kind of areas home to buckaroos. Saddles are very regional. They are, and always have been, regional. Between their saddle, tack and hat, you know where somebody is from.”

What makes a Wade a Wade?

“A Wade saddle fits lower on the horse,” he explained. “It has a slick fork with a prominent lip in the front and a large horn. It also tends to feature bars with a large surface area to help distribute the weight and to spread pressure more evenly across a horse’s back. It causes less stress on the horse. A Wade saddle is well suited to handle heavy, powerful animals out in range conditions.”

ENCOUNTERING A MASTER

For saddlemaker Geisler, 39, his charismatic role model since childhood has been legendary master saddlemaker, Dale Harwood. Geisler’s connection to the saddlemaker was linked to his paternal grandfather, the late Blair Geisler, a horseman and cowboy who ran a farm supply business in Idaho Falls, Idaho, where at one time, Harwood had his workshop.

“My grandfather knew Dale Harwood in the 1960s, before I was born. My first awareness of Dale was at about age 11, when my parents moved back to Idaho Falls in 1991, and I could visit Dale’s shop,” Geisler said.

“I met him personally. His shop never changed. It looked the same for years. Dale would always talk to my dad, Steve Geisler, a lariat rope manufacturer. When we’d go and visit Dale, he wouldn’t stop working. He’d hold one tool in his mouth, while he talked, but would never look up from his work.

“Dale is a man of small stature,” he added. “He has an old-world craftsman vibe. It wasn’t until I was in my 20s, that my visits became more personal. He was also a custom gun builder. He had high-level skills in woodworking and metalworking. I got interested in woodworking, so I’d go to Dale’s shop and talk a bit about making things from wood.”

In those early years, his interaction with Harwood was casual. “He wasn’t a mentor at that point. He was like a grandpa. I could go talk to him. He would occasionally teach me something in a casual way. He’s very free with his knowledge, but he’s not going to hold your hand. He expects you to figure out things for yourself.”

In 2006, Geisler earned a BBA degree in international business from Boise State University in Idaho. During his college years, he lived in Chengdu, in southwestern China, a region that borders Tibet. He went as an exchange student, from 2003 to 2004. He returned to the region, after graduation, in 2007 to 2008. “I learned Mandarin. In Chengdu, I saw a Tibetan saddle in an antique shop, bought it and sent it back to the U.S.”

When back in the states, he brought the antique saddle to Harwood. “He looked at it from the standpoint of how it was made and how the saddle would work for a horse. He was surprised that it looked like Native American saddles that he had seen,” he recalled.

“In 2015, Geisler and his fiancé, Brit Waters, a U.S. Army medical doctor who served in Afghanistan, decided to take the great American road trip during her post-deployment leave. “It was me and her, and her elderly dog, Roxie. By the time we got to Idaho, the dog had a ragged collar. We stopped at my dad’s leather shop. I got some materials and made Roxie a leather collar. That started the whole thing.”

Geisler and Waters were married in 2015. But earning a livelihood from leatherworking didn’t fully occur to him, until Brit made a timely suggestion. “Why don’t you go find your spirit animal? Make some leather stuff —make a few leather things?”

Soon, he began making and selling his leather goods and ordering more tools and supplies. He finished his five-year tour as an artillery field officer in the U.S. Army in 2017. He completed his service as a first lieutenant.

“Very early on, it all crystallized. I thought, if I’m going to be a leatherworker, I want to be a saddlemaker. It was central to my whole life — growing up around horses.”

He soon realized, however, that nothing was harder to make or more beautiful than a western saddle. “It offers you the most opportunity to showcase your skills,” he said. So, he called Dale Harwood and asked if he would teach him saddlemaking.

“He was not very enthusiastic. Ultimately, it took me two years to convince Dale that I was committed enough, and that I had good enough skills, to learn how to build a Wade saddle directly from him in his shop,” Geisler said.

His game-changing mentorship with Harwood began in earnest. “He coached me through the whole thing. He would hover over me, standing there with a toothpick in his mouth, and I’d sweat bullets. I watched his videos. I took 500 pictures and 50 pages of notes. I wanted to capture everything important,” he recalled.

“We built it together — my very first saddle, built under his direction. I used his tools, but he made me bring my own knives. He gave the saddle that I built with him, a tacit nod of approval.”

The saddlemaster also gave his student a humbling piece of wisdom. “You know, its going to take you quite a few saddles before you build another one that nice,” he said.

Geisler recounted how Harwood himself came to build genuine Wade saddles:

“In the early 1960s, the famed horseman, Ray Hunt, came to see Dale. He wanted Dale to make him a Wade saddle. But Dale needed to find a satisfactory saddletree. So, he went to learn how to make a genuine Wade tree from Walt Youngman, the head tree maker at Hamley & Co., in Pendleton, Oregon. In the process, Dale obtained the patterns for the original Wade — true to the original form,” Geisler said.

“I learned to build saddles from Dale Harwood, at a journeyman level — doing things his way, with his patterns and style. However, Dale was the product of a unique environment,” he reflected. “He was making saddles during the post-WWII cowboy scene, when there were still a lot of real cowboys left. I’m not Dale. I can’t bring back or relive what he did. But, I can take a look at what that was . . . re-interpret and breathe life into it, and bring it into the modern world.”

Altogether, Geisler makes about 16 saddles per year. “Dale said you’re not a full-time saddlemaker until you make 20 a year. I’m pretty close to full time. For me, I’m doing it despite the challenges of living.”

IT’S ALL IN THE DETAILS

To Geisler, what can’t be seen in a saddle’s construction is often more important than what can be seen.

“In my opinion, I use only the best materials. I have no interest in cutting costs. I pay strict attention to details that people don’t see. For example, when I’m working on saddle shaping and smoothing the ground seat, there’s a composite of four or five leather pieces. Nobody sees whether they’re nice or not. But, I try to make things as neat and clean and tidy as possible. I pay a lot of attention to details that won’t see the light of day.”

His saddle trees are sourced from Warren Wright Treemaker of Ohauiti, Tauranga, New Zealand. Wright trees use Canadian Douglas fir. “Warren’s trees are authentic to the original Wade tree,” Geisler said.

His saddles are built with heavy saddle skirting leather from Hermann Oak Leather Co. Latigo and strings are ordered from Horween Leather Co. Jeremiah Watt Products (JWP) crafts the saddlery’s stainless steel rigging plates.

“One of the secret weapons in my tool box are industrial trim knives from The Hyde Store, a company based in Fall River, Massachusetts. They’re economical, made for the factory shoe industry. I probably reach for those more than anything else. Where the rubber meets the road is stuff that works,” Geisler said.

He’s also fond of a saddle hammer once owned by the late, accomplished saddlemaker, Don King of Sheridan, Wyoming. And, Geisler still sews all his saddles on a World War I era, Randall Harness stitching machine. “Old harness machines are the only stitchers capable of using liquid wax thread. They pull the thread through a pot of liquid wax. I import linen thread from Europe. I buy 50 kilograms at a time.”

For long-term durability, he believes that waxed linen thread works best. “Linen thread is a weaker material than synthetic thread. But, when the liquid wax on the thread dries, it acts as a mechanical fastener, like a shoe peg. It holds together internally. You can see that effect in really well-made shoes. . . . Synthetic thread just doesn’t hold together in the same way. It will pull apart. Dale Harwood is convinced that saddles sewn with waxed linen thread hold better over time.”

STEADY GROWTH

Aspen Saddlery’s most popular saddle is the full rough out. They start at $4,000, but depending upon options like carving, tooling, silver or fancy stirrups, prices can go to $5,000 or more.

Sales are made almost exclusively by word of mouth. “Getting your work in front of a customer is the hardest battle — cultivating a customer base. I have a lot of repeat customers. Some have two, three or four of my saddles,” Geisler said.

Saddlemakers, he pointed out, have the duty to make saddles that work well for both horse and rider. “That’s what I like most about this craft. If the saddle doesn’t work, it doesn’t matter how beautiful it is.”

Saddlemaking is his primary business. To facilitate more income, however, he makes men’s leather travel bags, which start at $80. He ships about 200 to 300 travel bags per year across the country and globally, to places like Hong Kong, Kuwait, Turkey, UK, Canada and Mexico. Aspen Saddlery travel bags are sold in boutiques in places like Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

To achieve his goal to be a full-time saddlemaker, he is taking on less custom work outside of saddlebags, duffels and briefcases. “No dog collars. I don’t make wallets,” he said.

“It’s a lifestyle — making a saddle is a lot of work. In our society, there’s a perception that working with your hands isn’t dignified — or it’s blue collar. The fact is I make a good workman’s wages. It raises the quality of life here. And, I had to learn how to maintain and repair all my tools and equipment, and to build things like workbenches. There’s no retail solution for that,” he said.

Moreover, doing leatherwork in a home workshop gives him more time to be with his 3½-year-old son, Harrison, and his wife, Brit, he said, “something that a conventional job wouldn’t allow.”

Nonetheless, the saddlemaking population appears to be declining, he observed. “I’m one of the younger guys at the big leather shows, like the one in Sheridan, Wyoming,” he said, referring to the Rocky Mountain Leather Trade Show. “Very few people in my age range are doing what I’m doing.”

On the other hand, he believes there are more hobby leatherworkers now, than in the 1950s. “The amount and variety of tools and leather suppliers has to be double or triple what it once was. There is a wonderland of tools and materials. But, not very many saddlemakers.”

WHAT IT TAKES

In 2001, when Geisler was only 19 years old, he was involved in, as he described it, “a hideous motorcycle accident. My left leg was severed above the ankle. I had 10 surgeries on my left leg below the knee. They put it back on, a little short and little crooked.”

Amazingly, hard-earned fortitude and wisdom were born from that horrific ordeal. “Things happen for you, not to you. There’s nothing you can do about it. But you can choose to focus on what you can do now — to control your attitude. It’s very hard work. It’s especially hard when you’re a teenager,” he said.

He went through years of rehab. And, he spent a lot of time figuring out what he could do. In 2010, he joined the U.S. Army. In 2011, at age 29, he attended Officer Candidate School (OCS) in Fort Benning, Georgia. “It was a difficult course. Out of 188 people, about 80 were commissioned as a second lieutenant,” he said. He graduated that same year.

After graduation, he was assigned to the 3 d Cavalry Regiment. “It’s the second oldest, continuously serving unit in the Army. Originally, they used real horses. They went from horses, to tanks, to strikers. A cowboy hat is part of their uniform,” he said.

“I spent five years in the service of my country. I don’t want to glorify my service. I did my civic duty during wartime . . . I don’t want to take away from people who have done more important things, who have given more, sacrificed more. I did what I thought was important at the time. That doesn’t make me a hero,” he said.

RESILIENCE

In 2014, while at an U.S. Army training center near Death Valley, he met Brit Waters, an Army doctor specializing as an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN).

“I am married to a field grade military officer,” Geisler noted. “She served as a general surgeon in Afghanistan, as well as a medical advisor to Regional Command East (RCE), getting shot at with rockets and mortars pretty much every day of the year. She goes to work every day in uniform,” he said.

Their son was born in 2016, when the Geisler’s were stationed in Fort Wainright, Alaska, where Brit was assigned chief of the obstetric department at Bassett Army Community Hospital. Balancing child raising with work and marriage called for a new level of adaptability and personal largess.

“I was a working-at-home dad. I did all the cooking and most of the childcare. And, I was making saddlebags, and anything else, to grow my business. They had a Montessori school there, where Harrison could learn to be a good little human,” he said.

In 2019, Brit’s military career necessitated a move to Fort Knox, Kentucky. Pulling up stakes in Alaska meant moving Aspen Saddlery’s entire leather workshop to the township of Rineyville, located seven miles northwest of Elizabethtown.

“Discipline is the cornerstone of what I do. Our goals have to be complementary. You have to be on the same page with goals and desires. We both work out every day and create an environment of mutual support.”

The COVID pandemic has brought another level of challenges. “I’m busy enough with saddles. But with travel bags, many were set for weddings and special events. So, many orders have been postponed and there has been a decline,” he said. “Supply-side issues are also difficult. Tanneries are limiting production, so things bottleneck. Some imports have slowed down. Issues with the U.S. Postal Service are rampant. The non-saddle side of the business has been down about 50 percent, or more.”

On the plus side, Geisler sees an opportunity in downtime. “I can now develop the artistic side of saddlemaking. Saddles are so complex. There are so many parts. You don’t get a redo. You can’t untrim it and try again. You can only focus on improving one part at a time.

“It’s critical that every saddle you make reflects an improvement in some dimension. If you feel like you’ve got it together, you’re wrong,” he said.

Aspen Saddlery, Ben Geisler, owner, operator

P.O. Box 151, Rineyville, KY 40162

1-208-680-3264

benmgeisler@gmail.com

aspensaddlery.com

Instagram — @bmgeisler

HEROES AND HORSES

“It’s important that everybody does what they can do to serve their country,” said saddlemaker Ben Geisler, owner and operator of Aspen Saddlery of Rineyville, Kentucky.

Geisler served a five-year tour as an artillery field officer in the U.S. Army. In order to contribute to the well-being of those with whom he served, he became a supporter of Heroes and Horses, a Montana-based, non-profit organization founded by Micah Fink.

“They treat combat vets who have issues like PTSD, with equine therapy, leadership training and hands-on ranch work,” Geisler explained.

According to the group’s website, the organization’s goal “is to reintegrate combat veterans through an innovative, comprehensive and effective process that uses the wilderness, the horse-human connection and a proven leadership model.”

“Heroes and Horses offers an alternative solution for combat vets to redefine and approach their physical and mental scars — a solution that does not include prescription medications or traditional psychotherapy.”

Geisler has a working relationship with the organization. “I donated a saddle I made. And, I ran a marathon to raise funds. I am a saddlemaking sponsor. Especially in times like these, we need to support people helping people,” he said.

Heroes and Horses, 211 Jetway Drive, Unit Z2, Belgrade, MT 59714

(406) 284-2870

admin@heroesandhorses.org

heroesandhorses.org/

For an 8-minute, Heroes and Horses video:

This article originally appeared on Shop Talk Magazine and is published here with permission.

There are more interesting articles in our section on Tack & Farm.