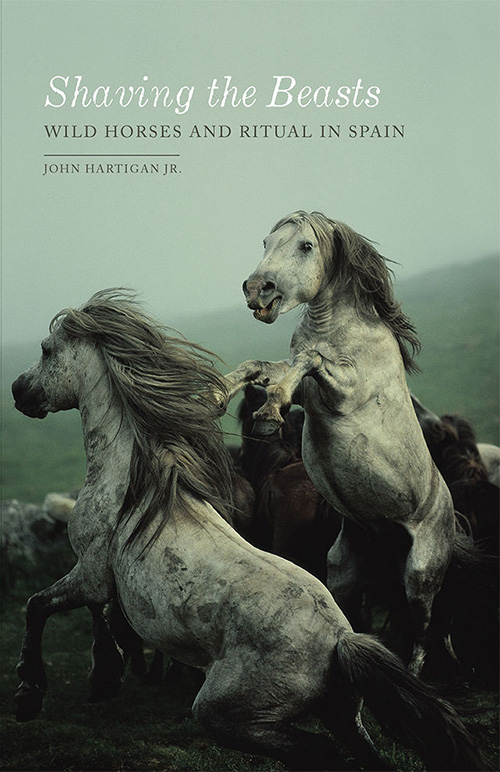

This is an excerpt from Shaving the Beasts: Wild Horses and Ritual in Spain by John Hartigan Jr., a vivid first-person study of a notorious equine ritual—from the perspective of the wild horses who are its targets.

Roughly eleven thousand horses roam the mountainous terrain of Galicia, Spain, in the northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula. They have inhabited these slopes for millennia and are one of the largest free-ranging populations in the world. Every summer in more than a dozen rural localities, many of these horses are rounded up in a ritual called rapa das bestas, or “shaving the beasts.” The earliest historical accounts of this ritual date to the 1500s, but archeologists argue that this tradition extends from the Neolithic era, based on petroglyphs fea-turing horses being driven into small rock enclosures. That is the heart of the rapa: wild horses, roaming communal lands in the mountains, are herded together and driven into curros—structures similar to rodeo corrals—where their manes and tails are systematically shaved. Their hair, which in the past had many folk uses, falls worthlessly to the ground.

Though they belong to Equus ferus, these animals are called bestas (beasts) or burras (asses), reflecting a widely held view that they are a de¬generate mountain breed. They are intensely disparaged and not con¬sidered “real” horses in comparison with the glorified Andalusians and other Spanish breeds. Smaller in stature than most of their conspecif¬ics, this population features a distinctive body type: they have relatively large bellies and short legs, some feature a distinctive gait, and a few sport a thick “mustache,” which is probably an adaptation to the thorny gorse they feed on extensively. These physical characteristics indicate that this population was certainly passed over by modern breeding re¬gimes, starting with royal projects in the 1400s. That is, rather than a degenerate strain, these are possibly a refuge population that survived when the last Ice Age decimated European horses. That would make them Equus ferus atlanticus, a distinct subspecies from Equus ferus caballus, the domesticated horse.

Their status as “wild” is complicated. They survive in the mountains by forage alone and are subject to intense predation by wolves. Their interactions with humans are limited to besteiros, who organize and conduct the rapa das bestas. The label besteiro identifies them as “beast keepers,” and some of the stigma attached to the horses adheres also to the humans who associate with them. Ownership of these animals—established through branding foals caught during the rapas—allows a person to claim subsequent offspring, which in turn might be sold. But there is little profit to be generated from such sales, and they often do not match recent costs imposed by the government for microchipping, registering, and insuring the horses. Many besteiros—mostly old men (60s and 70s), often with limited financial means—increasingly see ownership as an imperiled practice. For some, this precarious status makes preserving the tradition all the more important. Their efforts, though, are frequently pitted against wealthier villagers who see cattle as a more lucrative option and would like to have the horses removed entirely from communal parish lands. The Galician government, Xunta de Galicia, considers them a nuisance (due to rising insurance costs from car wrecks) and seems intent on regulating them out of existence. The government’s interests may be fueled by the increasing global no-toriety of the rapa das bestas, but more on that in a moment.

The basic technique by which these animals are herded is centuries old. People on foot and on horseback fan out in long lines that snake through woods, meadows, and tangled underbrush along mountain¬sides. With sticks in hand—sometimes well-worn and familiar canes, other times found and fashioned on the spot on the day of the event—they move forward, shouting and banging noise makers to roust the horses and drive them toward a catchment area. Historically, a similar technique was directed at wolves, who were then slaughtered at the culmination of the process. Deeper in time, this method is likely the means by which horses were first captured and domesticated. I was incredulous, initially, that slow-footed humans could catch horses this way. But they scare easily as the raucous line moves through the brush, and horses are loath to try to break through the cordon that forms around them as lines converge, close, and then encircle clusters of the creatures. Partly this is from fear of the swinging sticks and noise, but it is also a reflection of their social instinct to band together—individuals typically do not break through on their own.

The encircled horses are then driven toward a large fenced pasture where they are penned and given time to settle down. It is a period of confusion for the horses: bands have fragmented and they may struggle to reassemble and, most poignantly, mares and foals, separated in the ordeal, desperately search for each other. Frantic whinnies and plain¬tive cries rend the air as horses churn about and people course through the herd. Mostly these are besteiros looking to identify and claim new foals. They push horses aside to get at the targeted beasts, causing a cascade effect as displaced horses crash into others, generating alterca¬tions. Though they try to avoid such contact, transgressions of social space are often unavoidable, inviting bites and kicks from annoyed conspecifics. Spectators who show up to see these equines also move freely among them. This is an attraction for people who come out for the day to watch the rapa unfold. The curros are frequently ringed with pop-up kitchens housed in huge tents boasting long tables and fold¬ing chairs, where families and groups of friends, such as riding clubs, feed on large plates of freshly cooked octopus or grilled pork ribs and chicken. These kitchens also feature well-stocked bars, fueling a festive atmosphere for the humans.

After lunch, the hard work of the rapa begins—shearing the horses. This starts by moving them into the curro, a much smaller, tightly con¬fined space. These are traditionally stonewalled structures but some rapas now sport metal-fenced corrals. In any case, the next step is to extract the foals from among the adults. This process may take twenty minutes or longer, depending on the size of the herd. The larger rapas capture up to seven hundred horses, but most work with around two hundred or so. The earlier trauma of separation from the foals during the initial herding is revisited, only this time in far more frenzied fash¬ion because the adult horses are compressed together now; this makes the humans relatively safe from rearing animals, while profoundly dis¬turbing the horses’ keen sense of social space and distance. Aggressions flow freely, at least initially, as kicks and bites swirl about. After the foals are removed, the shaving begins.

For the shearing—the source of the ritual’s notoriety—techniques vary widely. In the south of Galicia, near the border with Portugal, the practice is to remove horses one by one from the curro using a rope cabestro that dangles from a hook at the end of a long pole called a vara. The rope is knotted to form two loops—one slips over the horse’s ears and the other closes on its mouth, making a halter. Then one person runs the horse out to the open pasture, where it is sheared and sprayed with an antiparasite treatment. At the end of this process, the horses are simply released singly to return to the range. Many bolt immediately from the grounds, heading up to the high country. Some mares may linger, hoping their foals will be released. For those with male offspring, that hope generally goes unfulfilled, since they are culled and sold for meat. This culling is more a matter of population control, to limit the size of herds, than a source of revenue. In the north and central areas of Galicia, in contrast, horses are mounted bareback and then shaved. The rapa near Viveiro, on the northern coast, features riders who jump onto the animals from the corral railings; they then take large metal hand-shears and methodically clip away at the mane from behind its neck. In Sabucedo, aloitadores, or “fighters,” take running leaps onto the horses’ backs from the ground; they ride the animal hard, driving it into the others, until it tires and then is tackled by several men, who pin it and hold it for the shearing. These horses, too, are then sprayed and microchipped, according to EU regulations.

In Sabucedo, a village of about three dozen people, this ritual is thoroughly elaborated and intensified. Unlike the others, this rapa takes place over several days, typically on the first weekend in July. Also, Sabucedo attracts tourists; often over ten thousand people, who camp in fields and woods about the village. The opening event is a mass for San Lorenzo, patron saint of Sabucedo, at 6 a.m. on Friday morning, after which locals and tourists alike (about a hundred people, initially; more join in over the course of the day) ascend the mountain in search of the bands. After a long morning of herding, followed by lunch in the field, the captured animals are driven down to the valley and then paraded through Sabucedo to the peche, an enclosure in a large hilltop pasture. Along the route, people crowd against or atop stone walls to watch the spectacle pass. Camera operators and film crews, many from other countries, dash about trying to capture vivid images of the pro¬cession. The narrow lane is also transformed with huge kitchens (each seating up to a hundred people) on one side and several carnival rides on the other. Vats of boiling water for the octopus and large charcoal grills for the other meats front the roadside, and narrow bar tops along the kitchen railings prop up increasingly drunk spectators.

About the Author John Hartigan Jr. is professor of anthropology and director of the Américo Paredes Center for Cultural Studies at the University of Texas, Austin.

"This excerpt from Shaving the Beasts: Wild Horses and Ritual in Spain by John Hartigan Jr. is reprinted by permission of the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2020 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota.

There are more interesting stories in our section on Recreation & Lifestyle.