William “Bill” Henry Knight is widely considered one of the greatest stampers of all time. Due to family obligations, he cut his stamping career short, leaving leatherwork at the height of his craft, at age 40. But before he did that, within a condensed 15-year period, he executed some of the most extraordinary examples of American leather carving and tooling ever made.

At 20, Bill apprenticed as a stamper at Rowell’s Ranch in Castro Valley, part of California’s Bay Area. There, Bill became immersed in the California-style stamping tradition, learning from craftsmen who had previously worked at California’s famous Visalia Stock Saddle Co.

Stanley Diaz—the most renowned California stamper of the era—worked at Rowell’s during Bill’s time there. Dave Silva, who later became Visalia’s last foreman and one of the most acclaimed saddle makers of the second half of the 20th century, apprenticed at Rowell’s at the same time as Bill.

It is unknown whether (and if so, to what extent) Diaz taught Bill how to stamp, but it is obvious that Diaz’s work—and the Visalia stamping tradition generally—had a profound influence on Bill.

Indeed, among Bill’s personal possessions, he kept, together with three Ray Holes Saddle Co. catalogues in which his work appeared (Numbers 48, 52 and 57), a 1942 Visalia advertisement depicting a finely tooled saddle very similar to the work Diaz was doing at the time.

While serving on the Sea of Japan during World War II, Bill honed his stamping skills during off-duty hours making stamping tools out of nails and other materials he could find. When Bill returned home to Idaho after the war, he intended to take up where he left off at Rowell’s by making a career in saddle making.

Over the next five years, at Ray Holes’ shop, Bill executed some of the finest examples of stamping ever published in a saddle shop catalog. The following decade, he stamped exquisite trophy saddles at Hamley’s & Co, including the 1959, “Oregon Centennial” saddle. Then, like the streak of his talent that hit the saddle making world in the 1940s, he was gone.

Bill was born on January 30, 1921, in New Plymouth, Idaho. His parents, Clarence and Viola Knight, had five children of whom Bill was the middle child. By all accounts, he grew up in a loving Idaho country household, where creativity, good works, self-sufficiency and family life were celebrated.

In his 80s, Bill took up journaling about his life. In his biographical essays, which demonstrate his artist’s touch, he wrote about his childhood.

Writing about his mother, Bill stated, “She was the most beautiful human I could imagine. She learned to cook and to sew and to love it I know, for she did it bettern’n anyone else. She loved gardening, for food and flowers.” “I never had a store-bought shirt while I lived at home,” he wrote, “same as Dad and both my brothers.”

Bill recalled “the pump in the yard of the country school, with its drinking cup hung on a wire hook,” and the “magpie nest in the cottonwoods down by the river.” “There was a slough almost stagnant, where you could almost always see a muskrat and out in the sagebrush, just across the irrigation canal, you’d scare up jack rabbits and once in a long while, a coyote,” he wrote.

In keeping with their idyllic home life, the Knight children grew up to be romantics—Bill’s older sister, Lois, was a gifted singer and piano player; his younger sister, Bonnie, and younger brother, Terry, were also singers and musicians; and his older brother, Buck, grew up to be a working cowboy who managed ranches all his life.

Bill loved the West. Recalling the times when he, Buck, and his father attended rodeos, Bill stated, “Dad was possibly classifiably a rodeo fan. He went and took brother Buck and me to convent rodeos in neighboring towns, until we grew familiar with the various events, and gradually with some of the more prominent contestants.”

Bill recalled the first time he attended the Pendleton Round-Up, stating, “Maybe I was about 13, the first time [Dad] took us to the Pendleton Round Up. That was definitely big time. There they saddled the bucking broncs right out in the arena, rather than inside a closed chute, making it more like a realistic ranch event.”

At the Pendleton Round Up, Bill watched three-time World All-Around Champion, Robert “Bob” A. Crosby, referred to as “King of the Cowboys” by Life magazine. Of Crosby, Bill said, he “was a big money winner at calf roping and maybe other timed events” and “hero worship welled up when he performed.”

Bill graduated from New Plymouth High School in 1939, after which he attended Boise Junior College (now known as Boise State University). As a young man, Bill aspired to become a writer and journalist.

During their courtship, Bill wrote his high school sweetheart and future wife, Sara Louise Tucker, a poem titled My Road— (February 14, 1938), which is reminiscent of Rudyard Kipling’s If— and just as powerful:

“I want to be the kind of man

That wants to live, and really can!

That is my ambition.

And when I’ve served my sentence out

I’ll face my maker without doubt

Of my position.

I want to live in such a way

That men who know me well can say:

“He never lied

To any fellow—fool or king,

But smiled—at death, and everything.”

You bet, I’ll have a home or bust

A love—an inter-family trust—

And then stick to it.

I want to be the type of lout

That I’d be proud to brag about—

—And then—Not do it!”

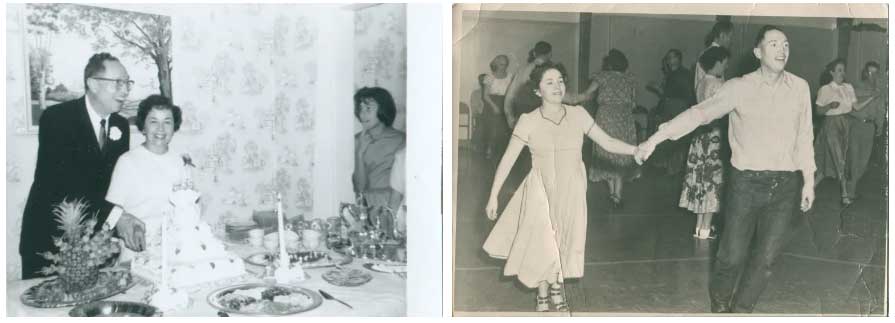

On July 8, 1940, Bill, age 19, married Sara, age 18. Sara, whose mother was from Mexico, was a devout Catholic. Bill, who was raised as a Methodist, also became a devout Catholic.

When the young couple started having children, Bill worried about being able to support them. They went to see a Catholic priest, about whether there might be any flexibility in the rules prohibiting the use of birth control. The priest essentially told them, “It is what it is.”

Bill and Sara eventually had seven children—six sons (three of whom studied for the priesthood, but ultimately opted for conventional family life) and a daughter.

In 1941, Bill started his stamping career with an apprenticeship at Harry Rowell’s Ranch in Castro Valley, California. Bill worked there with his then brother-in-law Steve Hoagland, a saddle maker, who had married Bill’s sister Lois during her time as a singer in the Bay Area.

Rowell, known as the “Rodeo King of the West,” arrived in the Bay Area in 1912, in his early 20s as a penniless Englishman. By the 1940s, he was living the American dream as the successful owner of slaughterhouses, a rancher and a rodeo producer and promoter—and founder of the famous Rowell Ranch Rodeo.

Rowell wanted to establish a saddle making business that would complement his other businesses. Following the standard modus operandi, he deployed to create his business empire; Rowell partnered with and hired the best workers he could find.

Rowell convinced Visalia’s foreman, Victor Alexander, to partner with him. In 1940, at Rowell Ranch, the two formed the Victor Alexander Company, with Alexander serving as president and Rowell as vice president.

Alexander, originally from Gallup/Ft. Wingate, New Mexico, previously worked on dude ranches and competed in the rodeo circuit throughout the country. After an injury in Miles City, Montana, Alexander joined Visalia in 1935 (then under the direction of Leland Bergen), and became Visalia’s foreman after five years.

When Alexander left Visalia for Rowell’s, a number of former Visalia workers followed him there, including stamper Stanley Diaz.

According to Victoria Carlyle Weiland and William A. Strobel’s Here’s A Go! Remembering Harry Rowell and the Rowell Ranch Rodeo, every worker at Rowell’s new saddle shop was “a specialist, whether silver or goldsmiths, engravers, leather toolers, wood workers who made the saddle trees, or spinners who spun the mohair from which the cinches and ropes were made.”

Weiland and Strobel state that, before the doors opened, the company had $20,000 worth of orders and a waiting list of 25 clients from Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, Nevada, the Midwest and Canada. Rowell secured lucrative contracts with Sears, Roebuck & Company to develop saddle lines for them. Bronc rider Fritz Truan, fresh after winning the prestigious Madison Square Garden saddle bronc riding title, placed the company’s first order, which was for a hand-tooled belt.

Thus, at the time Bill apprenticed at Rowell’s Ranch, it offered a unique environment for a young stamper interested in rodeos and the western lifestyle and tradition. Indeed, as proof of Rowell’s ability to attract talent, three of the greatest California style stampers—Stanley Diaz, Dave Silva and Bill Knight—all worked together at Rowell’s before World War II.

According to Silva, Diaz noticed Silva tooling backgrounds on saddles at the shop. Diaz told him, “Kid, you’re too good. You can do backgrounds on my stuff,” and from that point, Silva worked directly under Diaz.

Silva described Diaz as “one of the greatest rose stampers of all time, very likely the best rose tooler in the world.” Referring to the realism of Diaz’s work, Silva said, “You could almost reach in and pick them.”

According to Silva, the young stampers at Rowell’s envied his relationship with Diaz. It is very likely that Bill was one of those young stampers who watched in awe, as Diaz plied his trade with young Silva by his side.

The details of Bill’s relationship with Diaz are unknown. However, Diaz’s carving and tooling style – and more generally, the California stamping tradition which emphasized an effort at realism using specific flowers, buds and stems, developed at Visalia and other Bay Area saddle shops – made a tremendous impression on Bill.

Later in his career, when Bill’s admirers referred to him as a “master saddle maker,” he would balk. While Bill could make a saddle, he did not consider himself a master saddle maker.

But when his admirers referred to him as “a master stamper,” he beamed with pride and did not protest the point. After all, he was indeed a master stamper and had learned from, and worked alongside, some of the best in the history of the craft in America.

World War II interrupted the work of many of Rowell’s workers; Bill was no exception, despite his uneasiness about war. Along with Diaz, Silva and others at Rowell’s, Bill joined the war effort.

In May 1944, Bill was drafted into the Navy. He was stationed on a Navy mine sweeper in the Sea of Japan, where he saw combat in the dark of night.

Bill ascribed to the belief that he did not have the right to take the life of another human being, especially when, in his judgment, the human being he was “fighting” did not have free will concerning whether to fight back.

Bill’s inner-struggles with war are reflected in a letter to Sara, dated July 11, 1944, in which he wrote about the selection of his duty assignment. He wrote, “I guess I shall state Hospital Apprentice as my preference, + Chaplain’s Assistant + Yeoman as 2nd + 3rd choice—but I’m pessimistic about all that. I grow more indignantly a conscientious objector every day of my naval career.”

Bill accepted the assignment of radarman charged with detecting mines and submarines; he ultimately achieved the rank of Radarman 3rd Class (E-4). His letters home recounted details of submarine-chasing and mine-sweeping drills outside Pearl Harbor and quiet moments on the open ocean with sea creatures who visited him.

Bill wrote, “Mainly it was simply standing lookout watches together. Lookout watch is standing in the little enclosure on top of the wheelhouse with the whole sky overhead, and the great wide ocean all around. There were visitors that paid attention to us, like porpoises, which might spend hours diving back and forth across our bow, in small bunches.”

He continued, “Nowhere nearly as often, there’d be a school of larger beasts that Page [his shipmate] called ‘black fish,’ small whales, but not all that small either. They did not leap, as did the porpoises, but rhythmically rose to breach, more like ‘blow’ from the little valve they wore on top. They too would seem to adjust their speed to accompany us for hours. I’d wonder where they’d been, and also where’d they go.”

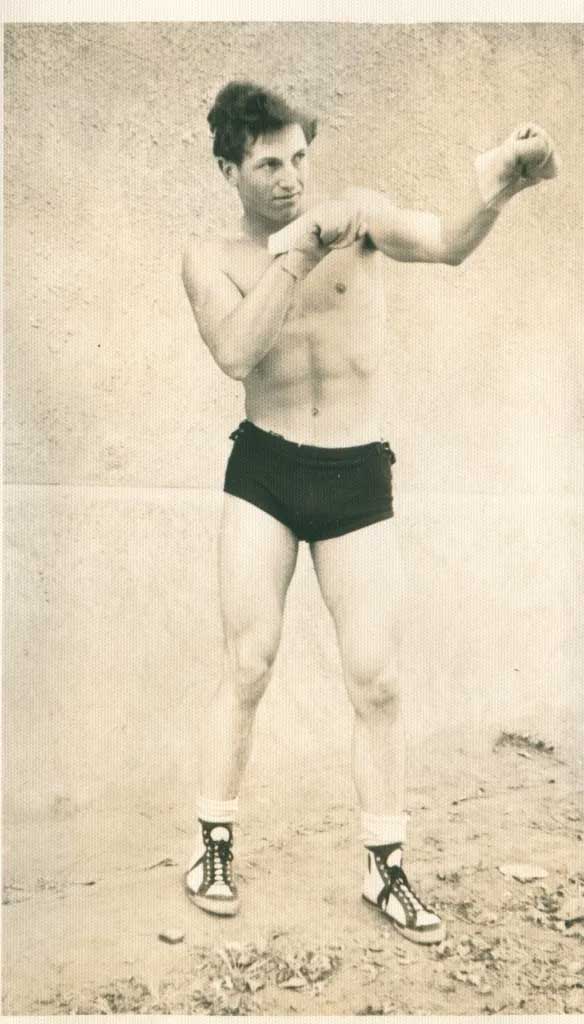

While none of Bill’s leatherwork from this period survived, he told his family that he continued to practice stamping in his free time. By this time, Bill displayed talent as a gifted artist. At their request, he gave his shipmates tattoos, even though he himself never had a tattoo. To pass the time, Bill also participated in Navy boxing matches.

Bill was honorably discharged from the Navy on November 14, 1945. After that, he returned home to Idaho and sought work in saddle shops. After seeing examples of his work, Ray Holes immediately hired Bill in 1945, under a program funded by the GI Bill.

Ray Holes, originally from Washington state, learned leatherwork in the 1930s at a state job training program for the disabled at George Lawrence Company in Portland, Oregon. From the mid-1930s through the early 1940s, Ray traveled to various places in the U.S. and Canada to learn more about stamping. His travels eventually led him to the Bay Area, where he befriended Olsen Nolte stamper Gene Sisco who shared with him information and designs relating to the California style.

A common misconception is that Ray Holes taught Bill Knight how to design, carve and tool leather. That is not so, and, actually, a strong case could be made that it was the other way around.

While Holes shared information with Bill he’d gathered during his travels to California (and also collaborated with Bill on some of the work done at Holes’ shop), Bill arrived as a full-fledged stamper. Indeed, Bill confided in friends that Ray even acknowledged to him that Bill’s stamping was superior.

Bill’s mastery of stamping in this period is evident in the now-famous “Copper Rose” panel (really, Bill’s rendition of the California style) that Bill designed and carved for the Ray Holes Saddle Co. catalog number 48.

According to the catalog, Holes registered the “Copper Rose” panel (page 17) for U.S. Patent protection on August 23, 1946—i.e., less than one year after Bill left the Navy—which means that, if the date in the catalog is accurate, Bill created the panel within one year of working at Holes’ shop.

The panel, which depicts a complex California style mixed floral, leaf, stem and bud design, is reminiscent of the famous so-called “Big Saddle” in Visalia Stock Saddle Company’s catalogue number 24. The “Big Saddle,” which is believed to be one of earliest examples of a highly intricate Visalia mixed floral design, is attributed to Visalia stamper Alfred Soria, who taught Stanley Diaz. Thus, it is very likely that Soria’s and Diaz’s work inspired Bill’s panel, and Bill may have even been practicing his rendition of Soria’s work while still in the Navy.

Bill’s stamped fenders (page 18), which have inspired generation upon generation of leather carvers and toolers throughout the world, were some of the finest examples of stamping work ever published at the time. The “IMPROVED TIPTON” saddle (page 5) and the “LEMHI” saddle (page 13), both of which are attributed to Bill, are two more exquisite examples of his work.

A common theme in Bill’s life is that those who came to know him, liked him. One story relates to a local rancher who stopped by Ray Holes’ shop to complain about a goat that was wreaking havoc on his ranch. Bill, who had a healthy opinion of his ability to tame animals, told the rancher he could get that goat under control. With that said, all the workers took their aprons off, locked the shop door and went to the rancher’s place. Bill promptly got into the pen with the goat, expecting to teach it a lesson, but after taking substantial abuse, he exited the pen filthy and covered in goat urine and was forced to acknowledge that goat had bested him. Decades later, people in the Northwest still laugh about the episode.

In August 1950, in an article titled “Craigmont Princess Will Use Resplendent Saddle in Entry Rides at Big Lewiston Roundup,” the Lewiston (Ida.) Morning Tribune featured one of Bill Knight’s Copper Rose saddles. While this particular saddle represented some of Bill’s best work at Holes’ shop, Bill was growing unhappy with his compensation.

By this time, Bill and Sara had five sons and another one on the way, and Bill was finding it difficult to make ends meet for the family. Even though Bill did the majority of the stamping work at Holes’ shop, Holes paid him as a “laborer” instead of as a “stamper.”

In September 1950, on the heels of their success at the Lewiston Roundup, Bill mustered up the courage to ask Ray for a stamper’s pay. As Bill later put it, he “protested a bit too loudly.” In response, Ray got angry and fired him.

After being fired, Bill called Hamley’s looking for a job and Hamley’s immediately hired him. As a testament to Bill’s extraordinary work—and proof of Bill’s supreme stamping at Holes’ shop—Bill’s work continued to appear in Ray Holes Saddle Co. catalogues for years, even though he no longer worked there.

Hamley’s scheduled Bill to start on October 1, 1950, but Bill did not leave for Pendleton until October 2, because he wanted to be present for his son Jim’s birthday on October 1.

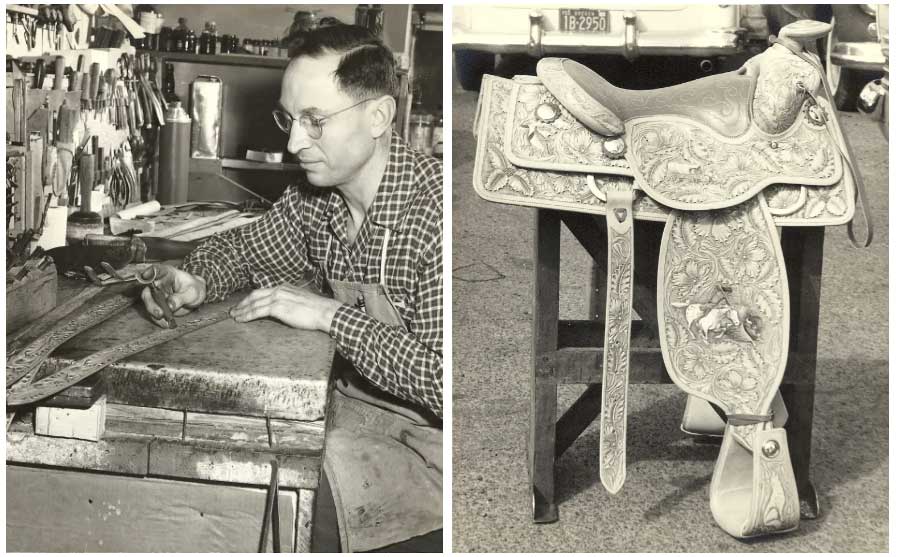

Bill worked for Hamley’s for approximately 11 years. During that time, Bill stamped all of Hamley’s trophy saddles and belts. In addition to stamping, Bill assumed the role of cutter, performed sewing and handled administrative duties. Bill’s colleagues appreciated the energy and talent he brought to the work.

Every Friday, Hamley’s had a custom of bringing out a bottle of booze that was stored in a hiding place in the basement. This was a time for the workers to let loose, sit around after work and visit about the week and their weekend plans. Bill and Sara often square danced as a couple at the local Pendleton dance club.

In 1955, Hamley’s promoted Bill to shop foreman. In that role, he earned $100 per week. Nevertheless, Bill grew concerned about his ability to care for his large family, which by that time consisted of all seven children.

From the stress, Bill developed stomach ulcers. At one point, Bill’s condition became so critical that he was taken by ambulance to the hospital. During his lengthy recovery, Hamley’s provided him full pay and medical coverage (a rare benefit in the saddle making industry at the time).

Just as Bill’s “stamping” elevated Ray Holes’ shop, Bill’s presence at Hamley’s solidified its reputation as one of the top saddle shops in the Northwest. Indeed, the first issue of The Leather Craftsman (Vol. I, No. I, 1956), dubbed Hamley’s “the foremost in western leather craftsmen.”

Another common misconception about Bill’s career is that Hamley’s undervalued him by giving him shop responsibilities (e.g., cutting, sewing and administrative work) other than stamping. But that is also wrong.

By taking on more responsibilities, Bill earned more money to provide for his family. At the same time, Bill’s seniority—and his tremendous reputation as a stamper—gave him the ability to “cherry pick” the best stamping work that came in the door.

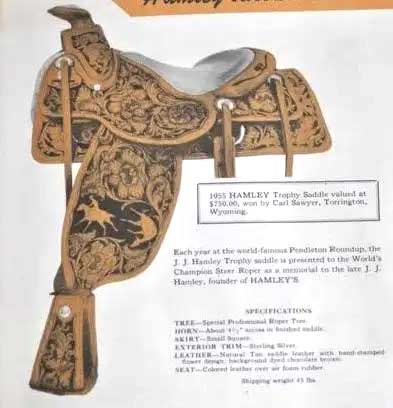

Every year since the founding of the Pendleton Round-Up in 1910, an event which J.J. Hamley helped organize, Hamley’s donated a fancy roper saddle as a trophy to the steer-roping champion. Thus, this Hamley’s tradition provided Bill the perfect platform for his extraordinary talent as a stamper, and the Pendleton Round-Up was a step up from the Lewiston Roundup.

An example of Bill’s legendary trophy saddles is his 1955 trophy saddle that appears on the cover of Hamley’s Catalogue No. 73.

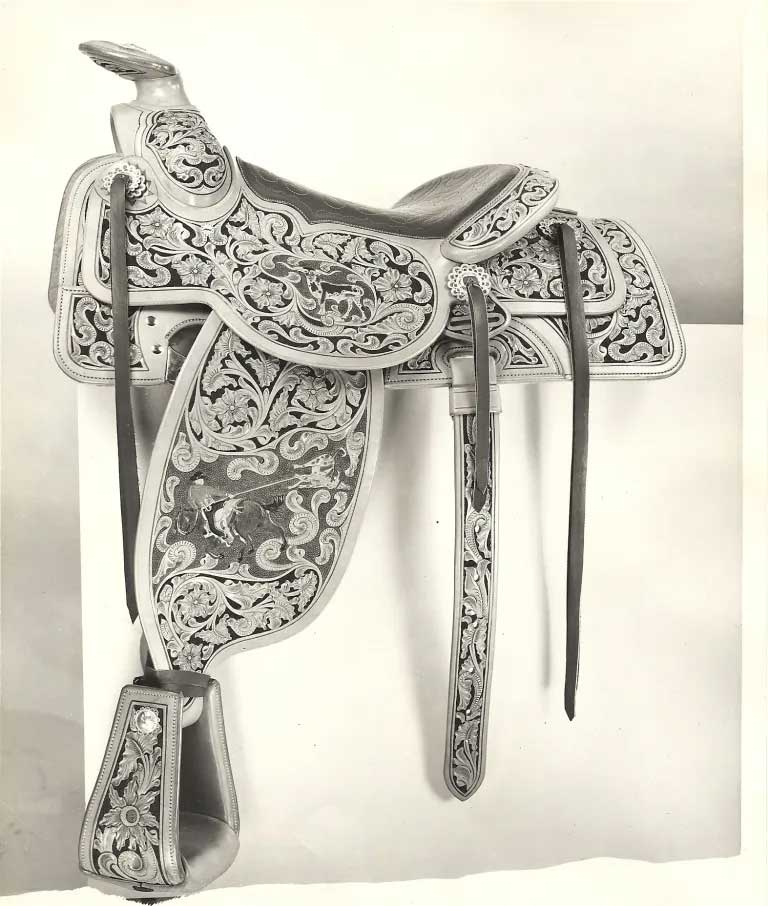

Bill’s life as a northwestern country boy, who first attended the Pendleton Round-Up as a teenager, came full circle when Hamley’s asked him to stamp the Pendleton Round-Up 1959 trophy saddle—arguably the most important saddle ever made in Oregon up to that point in time.

That saddle, known as the “Oregon Centennial” saddle, was special because it commemorated Oregon’s 100 years of statehood. Before Bill had even agreed to work on the saddle, Hamley’s and local civic leaders arranged for the saddle to be displayed at Hamley’s before the Round-Up and then go on tour throughout the state after the Round-Up was over.

When Hamley’s owner Lester Hamley asked Bill to stamp the “Oregon Centennial” saddle, Bill said he would do it if Hamley’s provided tickets for his family to attend all four days of the Pendleton Round-Up; in other words, he was thrilled to take on the challenge.

In an essay titled Pinnacle, Bill wrote about the experience, stating, “Every year at Roundup time, Hamley’s donated a fancy roper saddle as a trophy to the steer-roping champ. This was a tradition with lots of miles on it. Most years it was fitted with sterling silver mountings. This time it was to represent Oregon and her history.”

As requested, Bill designed and carved into the saddle the state bird (meadowlark), the state flower (Oregon grape), the state animal (beaver), a covered wagon and pioneers, an Indian buffalo hunter, a placer miner, a cowboy roping a steer, and howling coyotes. The saddle also featured the state colors—blue in the seat and gold in the stamped background and on the Oregon Centennial coin conches.

Bill, assisted by others in the shop, worked many hours to complete the saddle. The creases and tears on his Ray Holes Saddle Company Catalogue No. 57 suggest that he dug deep into his archives to make sure the Oregonian Saddle represented his best work.

Sister Mary Salesia, an Oregon pioneer and acclaimed artist who came to Oregon by wagon train before the turn of the century, painted the figures on the saddle. Sister Salesia served as the head of the art department at St. Joseph’s Academy, where Bill’s children attended school.

Just a few years earlier, a tragic fire consumed the main building and a small adjacent structure at St. Joseph’s Academy, where much of Sister Salesia’s life’s work was housed. The fire consumed thousands of dollars’ worth of oil paintings that had taken her years to create. The day after the fire, Sister Salesia wrote to her niece, stating, “Fire was climbing and lapping up over the outside when I first saw it. It was a sight I’ll never forget. Every one of the sisters got out safe – thank God no lives were lost. So, you see, we have much to be thankful for.”

Of Sister Salesia, Bill said, “The old nun was a sweetheart, and did marvelous painting on what must have been, for her, totally foreign ‘canvas.’”

Bill summed up his work, stating, “The gaudy trophy went on display in the front window [at Hamley’s] for all summer, much photographed. The daily newspaper featured it with pictures. For a sagebrush country farm kid, that was a pinnacle experience!”

The saddle, won by Joe Bergevin who later became a successful veterinarian, was the most significant of the 65 championship saddles made and donated by Hamley’s at the Pendleton Round-Up from 1910 through 1967. At the time of construction, the saddle was valued at $1,200.

Bill’s work, which is sometimes classified as “Northwest style carving” (as if it were wholly distinct from the California style), was groundbreaking because it took the California style in a new direction.

Bill showed that it was possible for someone (a Californian or otherwise) to take the California style and make it more “Californian,” in the sense that one could strive for greater realism.

While Visalia stamping already incorporated mixed floral patterns, cross-over stem transitions, and interlocking stems and scroll designs, Bill’s work placed greater emphasis on complex stem work than what typically appeared in Visalia’s stamped saddles at the time. Bill’s practice of carving his designs freehand, created a free-flowing, sometimes asymmetric design in his flowers and stem work that gives his stamping the appearance of greater realism, life and energy.

Idaho saddle maker and founding Traditional Cowboy Arts Association (TCAA) member, Cary Schwarz states, “Bill’s work that was pictured in the Ray Holes catalog has provided many generations of inspiration for leatherworkers and saddle makers.”

Explaining how Bill’s methods contributed to the development of his unique style, Schwarz states, “Bill Knight had a style of floral carving that was very spontaneous and had an organic feel to it. I believe this was a natural result of the way he cut his designs into the leather. He would simply make a small mark on the leather with the end of his swivel knife where he wanted flowers placed and then began cutting. The points provided just enough structure for him to take off and create a design that was unique to the particular project at hand.”

Summing up Bill’s monumental influence on floral carving and tooling, Colorado saddle maker John Willemsma, one of Schwarz’ fellow TCAA members, states, “We are all called to be a foundation for those that follow in our footsteps. Bill Knight’s work is an inspiration, and will be held as a foundation for all those who love fine floral carving.”

Business started to drop at Hamley’s in 1960. That year, Bill was the highest paid saddle maker at Hamley’s, earning $6,000 per year. Yet, it was not enough.

Speaking of his decision to leave Hamley’s, Bill said, “I loved the work, but I was finding that it was really hard to raise a family of six boys and one girl. Hamley’s paid me better than I could get paid elsewhere, but it just wasn’t enough.”

In 1961, Bill left Hamley’s to work for Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, first as a salesman and later as a successful agency manager. From 1961-1964, he worked in Pendleton, Oregon. In 1964, the company promoted him and transferred him to the Bay Area.

Bill, a hustler, excelled at his new work even though it was not a great fit for him personally. Starting out in a rented Oakland apartment, Bill was quickly able to afford homes in Hayward, and later in the Oakland Hills and eventually purchased rental properties.

In the early 1970s, a robber mugged Bill at gun point in a rough neighborhood in Oakland. The robber stole Bill’s hand-stamped briefcase he had made for himself before leaving Hamley’s, one of the last vestiges of Bill’s life as a preeminent master stamper.

This incident, combined with unending corporate pressures, caused Bill to suffer major depression and, shortly thereafter, he took a medical retirement. He managed his rental properties until Sara’s retirement from her work at a naval hospital.

During his retirement, Bill wrote an essay titled My Druthers, in which he described his favorite art forms. He stated, “I was a full-grown man before I ever heard a mariachi band. I was disgustedly walking the broken, filthy streets of Tijuana, Mexico, when strains of that haunting harmony floated over the urban scene, providing a quest for me. I had to scat around until I found them and stood enraptured.”

At the end of the essay, in one of the rare passages in which Bill touched upon his abilities as a leather craftsman, he wrote, “There is another form of rare art at which I personally became a master before the onset of gray hair, leather stamping. I apprenticed at the saddle trade and found my natural niche. There were several sub trades involved, but it was in flower stamping that I managed to excel. I frankly loved it and received reinforcing recognition through it. How rewarding to the ego!”

By this time, Bill must have believed that he had been forgotten except possibly by a few old-timers he knew from his days at the Ray Holes and Hamley’s shops. Thus, he was surprised to learn at a family reunion shortly after his 90th birthday that the Oregon Centennial saddle was on display at Hamley’s.

When Bill, Sara, and their son David visited Hamley’s to see the display in February 2011, the East Oregonian published an article about Bill’s visit, referring to him as “[t]he leathercrafting icon.” Parley Pearce, then co-owner of Hamley’s, and his staff treated the Knights like royalty.

Talking with the reporter about his work, Bill said simply, “I had good work and I was good at it.” Bill spoke about old friends including the champion bronc rider Casey Tibbs and renowned saddle maker Duff Severe (or Duffy, as Bill referred to him).

By this time, Bill had trouble seeing but he was pleased to hear that his work inspired generations of workers at Hamley’s. When a Hamley’s stamper handed him a tooled coin purse, Bill grinned and stated, “It feels like good work.”

Less than two years later, Bill passed away in his sleep on January 26, 2013.

Bill’s wife, Sara, is now 100. According to the Knight family, she is still going strong. In the meantime, Bill waits for her at their ultimate resting place, a set of grave stones commissioned by their sons. The grave stones depict images of Bill and Sara’s lives together: Mary and baby Jesus, Bill’s floral designs, a saddle and Bill’s hand holding a swivel knife—taken from a photograph of Bill carving a piece of leather in the days when he made stamping history.

This article originally appeared on Shoptalk Magazine and is published here with permission.

You can find all kinds of interesting articles in our section on Tack & Farm.